The following article originally appeared on Hawken School’s Redesigning High School site. The Mastery School of Hawken is a new PBL high school near Cleveland, Ohio built entirely around mastery learning. Korda’s methodology is the foundation of the educational and instructional framework of the Mastery School and she continues to work with their leadership team to help design the curriculum while training and coaching their teachers.

It’s Not About What We Teach, It’s About What They Learn

Think about a time when you surprised yourself by how well you were able to learn a challenging new thing. If you’re like most adults, what comes to mind is something like figuring out how to fix the broken video camera without any experience or trying over and over until finally getting the souffle just right – – but not something taught to you in an academic class.

Our entire approach to education – “stocking up” students with knowledge for them to use later – isn’t supported by the science about how humans learn. Science we’ve known for decades, but that the current education system has ignored.

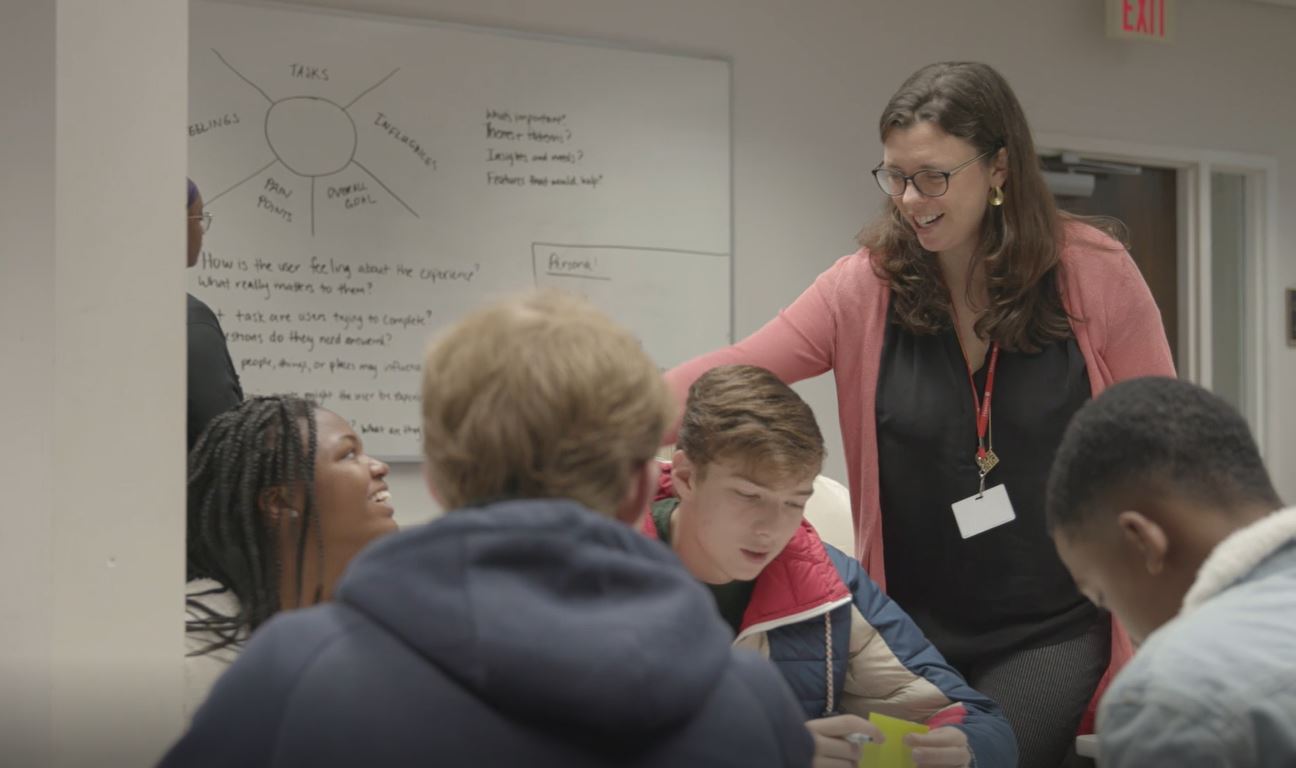

The method of teaching and learning we are using at Mastery School of Hawken has been developed over the course of decades in classrooms with thousands of students and is based on the cognitive science of how humans learn new things best. It has been implemented by hundreds of teachers whose students are learning every sort of subject matter while also developing the skills they need to thrive in education, work and life in the 21st century.

Consider two science projects assigned in different high school classes:

In the first, a teacher asked students to choose a toxic substance that exists in the environment and is harmful to human, plant or animal life. Their final assignment was a five-page report on the substance’s impact on health and the environment, as well as a poster-based presentation for a science fair-type exposition.

The second example is a science project from Hawken’s Entrepreneurial Studies class. The students left the classroom and were given a challenge by Rustbelt Riders, a Cleveland start-up, who was at a critical decision point in how to grow its composting business. The company was a small operation, run on a tight budget. Its three-person team picked up compostable waste from local restaurants and took it to an urban farm.

Their challenge to students: How can they “win” Cleveland – and make composting mainstream citywide? What new markets should they go after? Why and how should they pursue them? Students were put on teams and given three weeks to come up with evidence-based solutions for the company. Instead of a science fair project, they had to present their solutions to the Rustbelt Riders founders.

In the first, more typical, school project, students did online research, wrote a paper, and from it created a poster to show other students and their parents what they learned. Based on the research about what people retain, odds are that over time they will remember the toxic substance they chose and, if they found their chosen substance particularly interesting, maybe a fact or two about it.

The students creating business solutions for Rustbelt Riders had a much different experience. When they started their research, the students quickly discovered how complicated their task was. Before they could begin to think about a solution, they had to research topics like consumption patterns and how large-scale composting works in urban centers.

One student found what conditions were needed to create a sustainable program for separating and collecting compostable waste. Another student went deep into learning which food types were the most beneficial to compost and how to do it most effectively. Yet another student took it on himself to analyze and plan the most efficient routes for pickup and delivery of compostable material.

As they raced to develop a strong, data-backed solution, teams had to make hard choices about what to do – and what not to do – and how to go about it. They had to design their own process for problem-solving. Given their tight deadline, their success depended on the smart use of the individual strengths of their team members and mastery of the art and science of research: what sort of questions are best answered by online research? By surveys? By field research? Should they use structured, semi-structured, or unstructured techniques? How to discern good data from bad?

Unlike the students in the first example, who wrote reports, the students in this class learned new knowledge while solving Rustbelt Riders’ challenge that they will likely retain long after the course. And developed the kind of skills we know humans need to be successful in work and life: creative problem-solving, critical thinking, collaboration, learning how to learn.

That’s because humans learn new things best not by doing but while doing.

Learning from the Neuroscientists

Science shows that human learning isn’t sequential, and people don’t learn new things for keeps by memorizing, listening, or watching. That test you aced 10 years ago but would fail now because you can’t remember anything you memorized for it? That’s because you’re human.

Real learning changes us. Learning new things for keeps is something we talk about in education as learning for understanding and “transfer” – learning new things so well that you can apply them in other contexts.

Cognitive science supports what most of us understand about ourselves after a while: that humans learn hard new things best when they need to learn them in order to accomplish something they really care about. The most powerful learning – learning something new so well that it changes you — is an iterative, non-linear process.

In other words, it’s the exact opposite of how our current educational system is set up.

The Mastery School of Hawken uses a highly developed method of teaching that is based on the science of how humans learn new things best. Students learn while doing meaningful work as they solve real and urgent problems that involve and impact their community. Successfully tackling problems that don’t have answers in the back of the book, students develop the skills they need to thrive in this century, like creative problem-solving, collaboration, critical thinking.

And taught using a method based on the science of how humans learn best, students gain deep contextualized knowledge in every sort of discipline. Perhaps most important, they develop the substantive confidence that comes from learning how to learn difficult new things.

Which makes the learning deep, meaningful, and enduring.