In this episode, Doris speaks with Julia Griffin, Humanities teacher and Assistant Director of Teaching and Learning at Hawken Upper School. Julia shares how her humanities department adopted a new academic method that transformed the way their students learned ancient world history and better equipped them with skills like writing, research, critical thinking and public speaking.

Do School Better: A Podcast for People Who Want to Transform Education - Listen to more episodes here

Doris: Hello Julia.

Julia: Hey Doris.

Doris: Well, I am very excited about this conversation with you.

Julia: Me too.

Doris: Yes. And can you start by telling our listeners about yourself.

Julia: Sure. So, my name is Julia Griffin. And I am the Assistant Director of the Upper School for Teaching and Learning at Hawken School. I teach humanities and I actually started my career here at Hawken teaching Humanities these many, many years ago and was a Humanities teacher for a long time and then became Department Chair and then Assistant Director of the upper school last year. And along the way in those roles, I had the chance to do a lot of work with you in working on the Humanities curriculum which has been really great and has formed, you know, an increasing portion of my work with the curriculum with the school in the last few years.

Doris: Yeah, absolutely. I’d love for you to go back to when you came to me about the Humanities 9 class all those years ago. Describe what happened.

Julia: Absolutely. So, we were, you know, we were at a crossroads moment in the curriculum for Humanities 9…

Doris: This is ninth grade. The ninth grade require Humanities course so…

Julia: Exactly right.

Doris: …instead of History classes and English classes, our ninth graders at Hawken for many years and tenth graders have had a required Humanities course.

Julia: Exactly. And we were in a moment where…because of some changes in the schedule and then other aspects of the curriculum across the school, we were revisiting what we do in Humanities 9. And we were talking about different possibilities trying to figure out, you know, what to do that could help make the curriculum more engaging for students. It’s a course that focuses in most ways on the ancient worlds or on modern connections and the ancient world. And there’s a lot that is really valuable about it but it but it also can be a hard sell with ninth graders, right? Now, why should we care about these things that happened thousands of years ago? So, we were thinking about, you know, maybe it would be interesting to do something that was kind of problem-based or something that where the pedagogy was a little different. But we really weren’t sure how and I…

Doris: And tell me if this is true because my recollection of that also was, that it was both, you know, how do we make this stuff more engaging for students? And also, there was a question of we need to do a better job of developing our students skills like writing and critical thinking it’s…

Julia: And research and public speaking, like in a big way or a range of skills exactly that we felt were, you know, hard to teach and that could feel sort of diffused in the humanities classroom sometimes, that we’re sometimes that we’re trying to do so many different things all at once that we’re not always sure where that its landing with students.

Doris: Yeah.

Julia: So, that was another big part of the impetus. So then, what I remember is that you said, “Okay, great, let’s do this pilot. Which unit do the kids hate the most?”

Doris: Yes.

Julia: Right?

Doris: Yeah, what do they really hate the most? I didn’t say, is there something they don’t like. I said, “What do they hate the most?”

Julia: Right. Exactly. And I was like, “Well, I mean that’s not hard.” We have this China unit but it doesn’t really feel to anyone like it really works, but we want to do more with China not less. But we haven’t really figured out how to do that. And you said, you know, “How long do you have for it trying to pilot in the spring?”

Doris: Yes.

Julia: And I said, “We have about three weeks.” And you said, “Perfect. Great, let’s do it.” And so, we tried it. So we had eight…we had about eight sections of Humanities 9.

Doris: Yeah.

Julia: And we took three teachers, so three teachers and I worked on this initial pilot. And we tried it in those three sections, the other sections kept doing what they were doing. And then, at the end of the pilot, we surveyed the students who’d been in it and the student feedback was overwhelmingly positive. You know, it was…well over 90% of the students said, “Yes we absolutely think all ninth graders should have to do something like this as part of their ninth grade Humanities experience.” So we said, “Okay. Great. Good.” And we…and we built it into..

Doris: Yeah. I just wanted to know, so what did that evolve into? We did that pilot evolve into?

Julia: Yeah. So, that three week pilot formed the basis with some modest changes for what is the first you need of this semester course that ninth graders, that all ninth graders at Hawken take. That we call the Humanities 9 lab. And so, the content in the pilot was focused on China, and Chinese history and culture in this Humanities class. But what we ended up doing within the semester courses is that that courses focused on identity, and culture, and conflict in the Middle East.

Doris: Great.

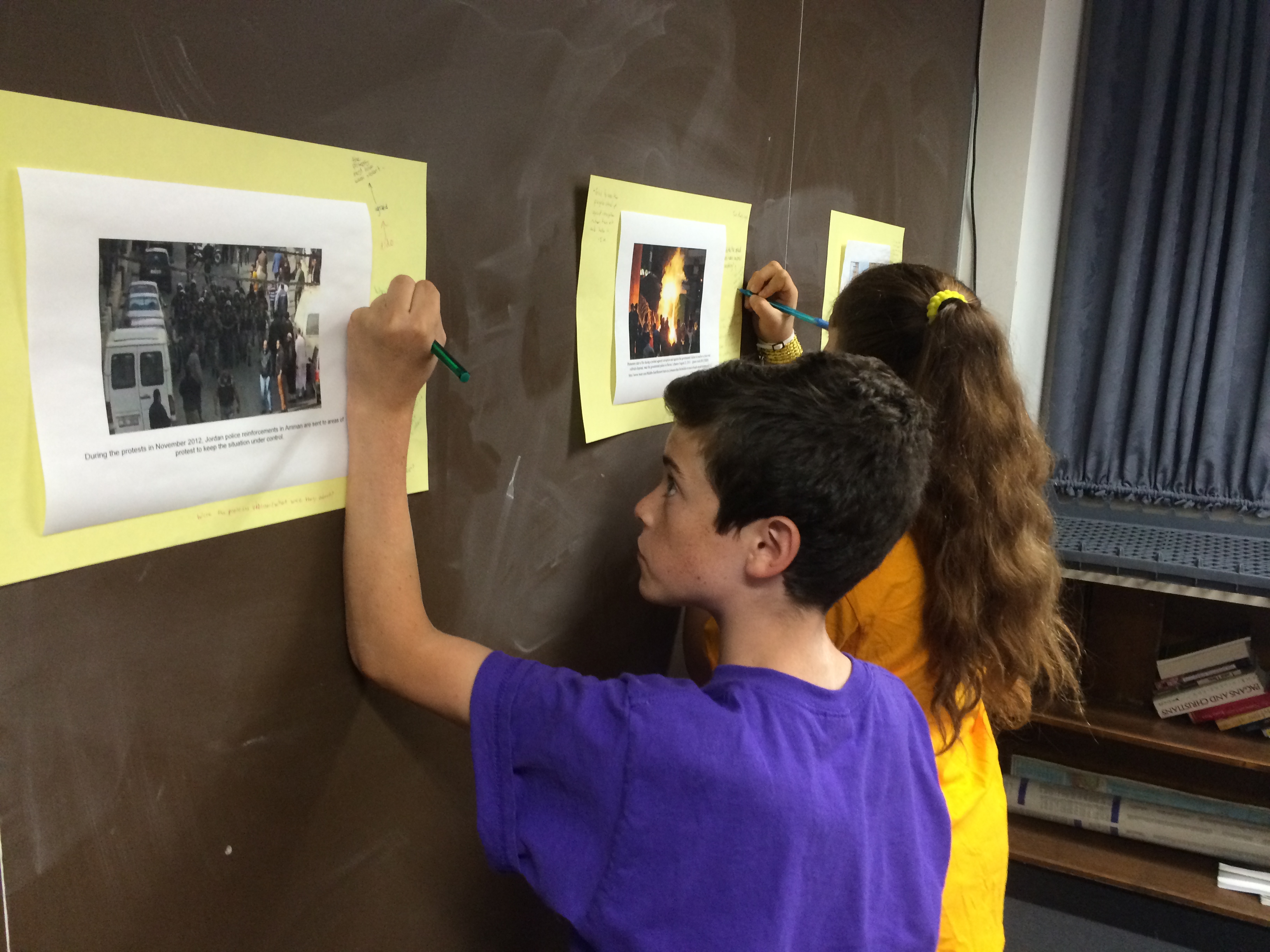

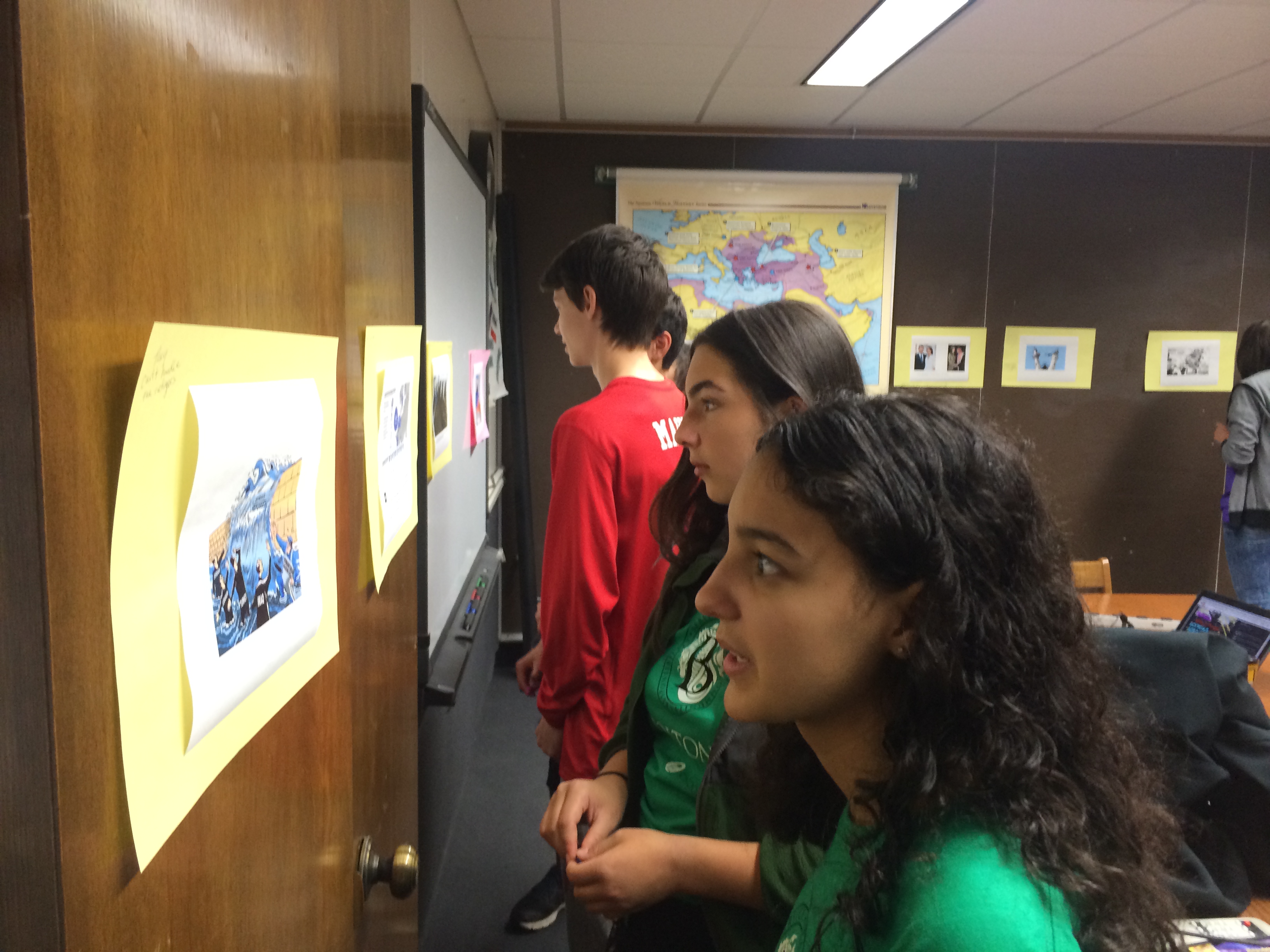

Julia: Yeah. So the way that we start the course begins where we…have the room set up as a museum. So, there are different artifacts all around the room, many of them images. So, we’ll have photographs, and maps, and graphs and charts, news articles, things that are just, have just been pulled from news in the last few days to a week. Books, set out on the tables often will have some music playing so…and content wise the museum as we call it, involves a little bit each semester partly because the news changes, right? So will have some photographs and some might be like a really urban setting and others might be, you know, UNESCO world heritage site.

Doris: Sure.

Julia: You know, out somewhere in the desert. Or we try to have some images that students are going to really know what to do with right, things that are puzzling. Sometimes we have a caption on them sometimes we don’t. And we try to have some images that are going to complicate whatever story. We think many students may be coming into the class with about the Middle East. So, we have a real range and we spend about 10 or 15 minutes like that, there are maybe 50 or 60 artifacts up usually.

Doris: Yeah.

Julia: So, they don’t necessarily get to all of them. And then, we say, “Great. So, for tomorrow, we’d like you to develop a one minute pitch designed to persuade your classmates of what topic you think we should study further and to compel them to vote for your topic. To have that form the basis for our first unit of study in this course. So, you’re going to decide what we what we learn about. And we want you to write this one-minute pitch.” And then we say so, “How do you think you should go about writing that? How would you be able to learn more in order to…? What else do you need to know in order to write a one minute pitch?” And, we get them started a little bit in class and then they work on it for homework and come back in.

They’re really excited on the next day when they come here to pitch. They’re all revising their pitch and trying to figure it out. And it’s really fun to see because they pitched whatever the topic is. And some of them are really nervous because they have to get up and do this one-minute talk for the class. So, they pitch to the class, the whole class votes on which topics are of the most interest. And we sort the students based on their preferences into usually about four teams of four roughly for the topics that they’re going to be exploring in that unit.

And that topics range and, you know, and it varies from semester to semester, it depends on what catches kid’s interest. So, you know, often times there’s one especially in the sort of first unit where there’s something related to ISIS. These kids hear about it in the news, especially I would say, a couple of years ago when we were starting with this and it was like it was in the news all the time and just in the weeks leading up to the course, you know, ISIS was blowing up world heritage sites some things like that, but often there’s something, so there’s something that’s sort of ISIS or terrorism related.

Doris: Yeah.

Julia: But then there are other things like, there would be one that’s about, you know, gender equality or there was one a couple years ago, it was really interesting about a trash crisis in Lebanon. So, that…and then it turned out that as they were these piles of trash, that was an artifact that had, there was just these pictures of trash piling up in the streets of Beirut. And, they wanted to figure out why.

So, there are a whole range of topics, they pitch, they have these teams and then, as they get into their teams they have a couple of tasks, right? So, one of them is to figure out how they’re going to work together as a team and what that means. And then, another piece is, how do we start to try to figure out what this problem is? Or what this…what the situation is that’s happening in the Middle East right now and how it got to be that way.

So, we try to establish some team norms and have them reflect on themselves, what they themselves are like and what kind of skills they bring to a team setting. And then, we say, “Okay and, you know, a week and a half, your job is to present back to this class and to me about the history of this problem, where did this come from and how did it get to be a problem and what is it? What is most important for us to know about that?” So, the big task for them at that point is to figure out, how do we learn and what we need to know in order to be able to present this back to an audience together in a way that makes sense.

Doris: So, let me ask you something, you now used the word problem and I want to ask what the students were…so it’s one thing to say, “Okay, this is what I want to study. And we voted for it and now we’re all going to study it.”

Julia: Yes.

Doris: But it’s more than that. These teams when they choose the trash, they’re choosing problems that they want to not only understand but they want to be able to address and present something…

Julia: Yes.

Doris: …with their own, you know, maybe not the end all solution but as a solution to the problem. Correct?

Julia: Yes. Exactly. And because that problem formulation and I would say we wrestle with this. Because we’ve…there’s a trap here, right? With 14-year old if you’re saying like, “Oh, you’re going to go solve the problems of the Middle East” like there’s a cultural imperialism piece there and there’s a…

Doris: Sure. Absolutely.

Julia: “Oh, we can solve all the problems of this region, we fixed it. Good. Now we can go out to soccer practice.”

Doris: Yeah, exactly.

Julia: Cause a danger there. But there’s nothing that gets students to engage or that has the kind of teeth that we needed to have. If there isn’t a problem, you know what I mean?

Doris: Yeah.

Julia: It is just…it’s like, here’s our book report on the topic. It just doesn’t work. It isn’t nearly as engaging.

Doris: Well, and I think this is really important though, for the listeners to understand. So, if I’m a Humanities teacher, this isn’t about simply saying, all right, students are choosing what they want to study which by itself is pretty interesting.

Julia: Right.

Doris: It’s literally, this is a problem in the Middle East that I’m really…

Julia: Yes.

Doris: …really interested in. And so, is everybody on my team. We are really jazzed about it and we’re going to take on understanding this problem. And, while, you’re right, you’re not telling them, “We are tasking you 14-year olds with solving the ISIS problem in three weeks.” They’re working on a really tough problem that is not solved and they’re going to present as a team about it in a way that invites their version of solutions.

Julia: Exactly. So one of the questions that we ask is, “Why hasn’t this problem been solved yet?”

Doris: Yeah.

Julia: That’s huge, right? So students tackling ISIS, the first thing students will come up with when they’re trying to say like, “What should be done to solve this problem?” is… some student in the group will say, “Well, you know, we just need to bomb the ISIS headquarters.” Like, you know, it’s a tough job but somebody has to do it right? So, some are going to say, “Okay. Well, if it were that simple then why hasn’t someone done that, right?” Do you think no one else was thinking about this? Probably there are some other people trying to solve these problems like…so, the first five solutions you come up with, that you need to then really then dig into why haven’t those solutions worked…

Doris: Well, and…

Julia: …because if it was that easily, right? Like someone would have figured that out.

Doris: Well, and this reminds me of our very earliest conversations when we were first talking about creating the China pilot. Also, where I remember saying, “If you go to Hawken school for your entire K-12 school experience, this is only three weeks that we at Hawken teach Chinese history.” Is a student going to come out of the three weeks no matter how we teach it… You know, even if they successfully memorize everything a teacher puts in front of them… are they going to come out of that well educated on Chinese history and the answer is well, of course not.

Julia: No

Doris: No. So, the question is if in three weeks, in one three week unit, you can get kids to come out to that three weeks going, “Oh wow! Chinese history, even really distant Chinese history is not only interesting to me, it’s actually really relevant as well. And when they are working on addressing a contemporary Chinese problem, can you get them to go deep in the way that they’re solving that or addressing it in order for it to be a quality job, in order for them to be successful at what they come up with in three weeks. They will have had, it has to be based in the cultural and historical context that the contemporary problem has emerged from. And the answers of course you can. Well, that’s what you’re talking about.

Julia: Exactly.

Doris: So they come in and they’re 14 years old and they can tell you in about two minutes, “Yeah, we can solve this, let’s just bomb them”.

Julia: Right.

Doris: And where the…the secret sauce in engaging them in caring about all this is everything you just described and how you’re setting it up. But they’re learning, that the learning that you’re getting them to do comes from the questions, and the prodding, and the guidance that you’re doing as you teach them so that they have to go deeper and deeper in order to come up with well put together and analyzed arguments.

Julia: Absolutely. And that’s also why we have an earlier presentation like a sort of a first checkpoint point, that one is really all about defining what the problem is and how it got to be that way. And the second presentation is all about the solutions because the other thing is that students are very quick to jump to the solutions.

Doris: Always. Every time.

Julia: And then…

Doris: So are adults by the way, everybody is.

Julia: It’s true, we all are, right?

Doris: Yeah.

Julia: And so, if we’re not careful like 17 seconds after they’ve pitched and formed their teams, some kid has opened up PowerPoint and is already trying to like make a slides for the final presentation and you’re like, “Whoa! We are so not there.” Right. So…

Doris: That’s brilliant. So the first one, they’re not even allowed to go there. They have a presentation to do and it doesn’t even you’re not even asking them to come up with any solution. They just have to present the problem.

Julia: Right. Exactly. It’s like you have to actually deeply understand the problem and where the problem comes from, right? So if we go back to the stinking trash in the streets of Lebanon for a minute, which by the way, like, I think if you’re 14 you’re like, “Huh, there’s all this trash in the street.” and at that moment, like literally there’s this big social media campaign “#youstink” that was designed to try to get to raise awareness for this. So there’s a problem there clearly and it’s interesting. So they were trying to figure it out and we had this great moment where they’re in class and then they were looking, and they were looking at social media and they’re like “Oh, there’s a protest happening right now.” And someone was, you know, live streaming it, and it was happening right now. So it couldn’t be any more immediate than that.

But then, they tried to get into it. They’re like, “Why didn’t somebody just pick up the trash?” Well, it turns out there’s no president of Lebanon right now. Like, they have an office for the president but they don’t have a president. “Well, why don’t they have a president?” “Well, the last president was sent to jail for corruption charges and they haven’t been able to elect a new one.” And they’re like. And I said, “Why haven’t they been able to elect a new one? Like, how hard is it?” And they’re like, “Hmm,” you know, and they’re looking there, looking in everything and then one of them says, “Well, there’s something about, like there’s a religious requirement, like the president has to be of a particular religion.” I’m like, “Really? Interesting. Interestingly weird. We don’t have that in this country, do we? No. Okay. So tell me more about that.”

So they’re trying to figure it out and then it turns out they get into all these details about the Lebanese political system, which by the way, I had only read about the day before. Like, I’m not an expert in Lebanese politics but I had tried to get into it the day before when I knew this was going to be a topic.

Doris: Yeah. We say that this is all about, as a teacher you have to stay one step ahead of them. That’s it.

Julia: Exactly. So it turned out that there are these quotas hit for the many political offices in Lebanon that are designed to sort of maintain balance between different religious groups. But then through…as I continued to ask them questions, like, they had read an article about that but they didn’t really get it or they didn’t really get why it mattered. But then, as you start to look at this and you’re like, “Oh okay, so the president needs to be of this religious backgrounds, but are there any eligible candidates or suitable candidates who are of that religious background.” Like, they still be kept going further into it and then they started to see the ways in which the, you know, legislative body was deadlocked and they had to have 40% of this and 40% of that in terms of the composition of the group. And that they started to figure all of that out and then I said, “Well, huh. Why is there that kind of religious diversity, you know, in Lebanon? Like, where does that come from?” You know, and then they start to try to figure out, like, “Well, how long has Lebanon been a country?” I mean, like, “Hugh.” And we start looking and they realized “Since when Lebanon has been, whatever, the 1940, 1950s?” And they start…as they go, they start to figure out like the colonial legacy and they start to get into all these really interesting questions about religious dynamics of that region, and of Lebanon particularly. And so then, all of a sudden, they’re really interested because somehow all of this leads back to why no one has been able to clean up the trash.

Doris: Exactly. But here’s what you did. So you set them up, they’ve got an unsolved problem that they’ve chosen, that they care a lot about and it’s real.

Julia: Right.

Doris: They’re going to be presenting to a real audience and you’ll get to that in a minute, a solution, but you as a teacher you’re keeping them where they need to be by staying one step ahead and asking good why questions, right? They just keep asking good why questions. Coming out the other end, I bet the students at least in my experience, the students barely remember you were there. It all came from them. But you’re getting them to go deep into the areas that they need to go so that they can come up with something in there in the meantime. That’s great. So keep going. So then what?

Julia: Right. So they do this presentation that’s defining the problem. Then there’s a moment where they sort of split to go a little bit more individually into a kind of deep dive into what they think a good solution could be. So after they, you know, do the first presentation, they get feedback, they reflect on that. Then they spend a couple of days researching individually and writing a position paper about what they think the best solution would be. They come back to their team. They share their papers. They share their solutions and their ideas and then they have this really great moment of kind of negotiating it out and talking as a team and sort of sorting through and arguing through you know pros and cons and elements. Almost always they end up bringing in elements of different people solutions. It’s not that you know one person’s solution somehow magically was just right. So they are sharing sources that they found at this point and then running into sources that disagree with each other and trying to navigate that and what do they do with that.

And ultimately then, putting together a final presentation, which is going to recap the sort of history and definition of a problem briefly but move into the solution. And for that presentation then, we bring in whoever else we can find. We’ll bring in other faculty or, you know, if and when we can get them other sort of parents or community members who are interested in the topic…

Doris: And why is this important. Why is it it’s so important. But why do you think it’s important that you bring in people that’s not just teachers and parents that they’re going to present their final solution to?

Julia: Well, because it raises the stakes so much, right, for students, especially if they think there are people who know more than they do about the topic.

Doris: Yeah? Exactly.

Julia: Right. People who, like, someone who really knows their stuff that clarifies the mind wonderfully right around like they need to work on this task because, you know, like your parents are going to say that it was great no matter what you do. But the idea that there is this, there is somebody who has some expertise in the field and might ask you a really tricky question. And, you know, you’re going to look silly if you don’t really have a good solution.

Doris: Yeah. You have to do your homework. You have to have some research and facts to back up where you came up with. You can’t just blow through it, right?

Julia: Exactly.

Doris: That’s great. So coming out of the reason all this is happening is, what did you experience? What did the students experience coming out of this, and what did the teachers see as the results of this? Why is it spreading at Hawken so much?

Julia: Yeah. So 2015 and 16 was the first year of Humanities 9, right?

Doris: Yeah.

Julia: So then, those ninth graders then were in 10th grade this past year, and members of the Humanities 10 team started to come up to us in the halls and say, “Oh my gosh.” We had this research project and they blew it out of the water like they did such a good job, they asked these great questions, like, they knew how to try to find sources and find answers…or they’re going to be like, “Oh my goodness the public speaking was so much better out of the gate right away, we didn’t even know what to do with ourselves.”

So they clearly…other teachers who didn’t even necessarily know a lot about what was going on in Hum. 9 Lab got interest because they saw the impact for students. And so that, within our department, is really where the conversation has moved to, is, “Okay, how can we do some more of this kind of work with kids? And then, you know, as you know, there are other pockets where this work is starting to happen across the upper school.

Doris: Yeah, talk about what you’re doing in the upper school in your new role where you’re not only leading the Humanities department but now our entire upper school curriculum…

Julia: Yeah. So, I mean, it’s really exciting. It’s been great for me to get to expand my view of the school beyond the Humanities department, and to get to start to partner with teachers in different departments. So, I’m continuing to get to have conversations with people who are really eager and excited to try something different and to really try to focus on, like, you know, what happens when you’re really focused on the sort of, the individual needs of a student, and how can you give them feedback that helps them do the learning that they need to do. And the Korda Method approach is just honestly the best way that I have found to be able to give students that opportunity to grow. And so, that’s really what I’m trying to do is in working with teachers and to get them to find a way.

Doris: And isn’t it… Yeah, it used to be and it’s still transitioning from this, but being a good teacher meant being a good master of your domain and the domain was some content area. And the definition of good teaching and what it is to teach is changing. And I’m so glad that it is because, look at the things you’ve done with your Humanities team, look at their kinds of things all these teachers at Hawken are building together with other teachers, together with you, it’s fantastic.

Julia: Well, it’s incredibly exciting because it continually reminds us that it’s not about us? It’s not about me and how much I love this Wordsworth poem or this Charlotte Perkins Gilman short story or the state like, “I used to wonder as a teacher why it was that sometimes I felt like I was the worst teacher when I was teaching something that I myself really loved.” Like, I used to have this problem with, like with Thoreau and Emerson, I would go in and I would be like so off the charts excited and the students be like, “Meh,” right? But that was in those moments it was about me, right? It was about like my love of Thoreau. And that is why it wasn’t working.

Doris: Yeah, exactly. And the line that, you know, I’m going to use even though people who’ve been working closely with me, like you, Alison and Tim, a lot of others who would probably throw up in their mouth because you’ve heard it so much. It’s not about what you teach. It’s about what they learn. And the interesting thing to me was that that idea for many years was actually a profound idea. It sounds so, like matter of fact well, “Duh” of course that’s true. But it’s actually kind of embodies this shift that we’re talking about.

Julia: It does.

Doris: And it’s really exciting. Julia, it was phenomenal to talk to you. Your work is brilliant and I’m so…

Julia: Oh my goodness. Thank you. Thank you so much for all of your help.

Doris: Well, I love working with you and I look forward to the work we’re going to continue to do together.

Julia: Me too.

Doris: Yay.

Julia: Yay. Thank you.