IF THERE WERE NO SCHOOL, BUT CHILDREN LEARNED THE STORIES OF HISTORY,

WE WOULD HAVE A WELL-EDUCATED SOCIETY.

You’ve heard Edmund Burke’s quote, “those who don’t learn history are doomed to repeat it.” And you’ve likely seen the roving reporters asking 20 random American college students and finding 17 of them couldn’t correctly identify who fought in the Civil War. Or World War II, or Vietnam, or…How can that be? What high school did they go to? Why aren’t we teaching history anymore?I can’t count the number of times in my 22 years of teaching that I’ve seen some version of this: a graduating senior says “I never learned that” when it becomes evident they’re completely unfamiliar with something that many would consider elementary (like the three branches of US government or neutrons or Darwin or…). A teacher overhears and becomes upset, saying, “Hold on – not true! Jimmy was in my 10th grade Class and I had an entire unit on the three branches of US government/molecules/Darwin.” To which I have always had the same response, either out loud or in my head: “it’s not about what you teach, it’s about what they learn.”

HISTORY IS STORIES. WHAT HAPPENED…HOW THINGS CAME TO BE…PEOPLE DOING THINGS THAT SOMEHOW CHANGED OUR WORLD. HUMANS ARE CONSTITUTIONALLY CURIOUS AND WE ARE WIRED TO LOVE STORIES. BUT NOT EVERYONE IS CURIOUS ABOUT THE SAME THINGS AND NOT EVERYONE LIKES THE SAME STORIES.

We have an immense amount of research now to support what anyone who’s been through school knows – that we don’t learn things best for keeps by memorizing and regurgitating. Yet we still measure academic achievement on the basis of standardized tests that require just that, including in the case of history.“Here’s a ton of stuff about the Civil War that you’ll need to know for your test next Friday.” They memorize it all Thursday night, do well on Friday, and then we’re surprised when three years later they don’t remember even having heard of the Confederates.

Thanks to technology, the history textbooks that most school teachers still use are completely unnecessary. What is necessary? Capturing the interest and imagination of each child so that they’re curious about how things came to be.So that they discover stories that satisfy their curiosity about something they’re interested in learning about. Which may not be the same thing the teacher finds interesting, or other students find interesting, but that results in each child realizing that they’re actually fascinated by history, and that they can easily learn it. This is a story about how my very different method of teaching changed the way 31 girls are learning history in a public middle school in Columbus, Ohio.

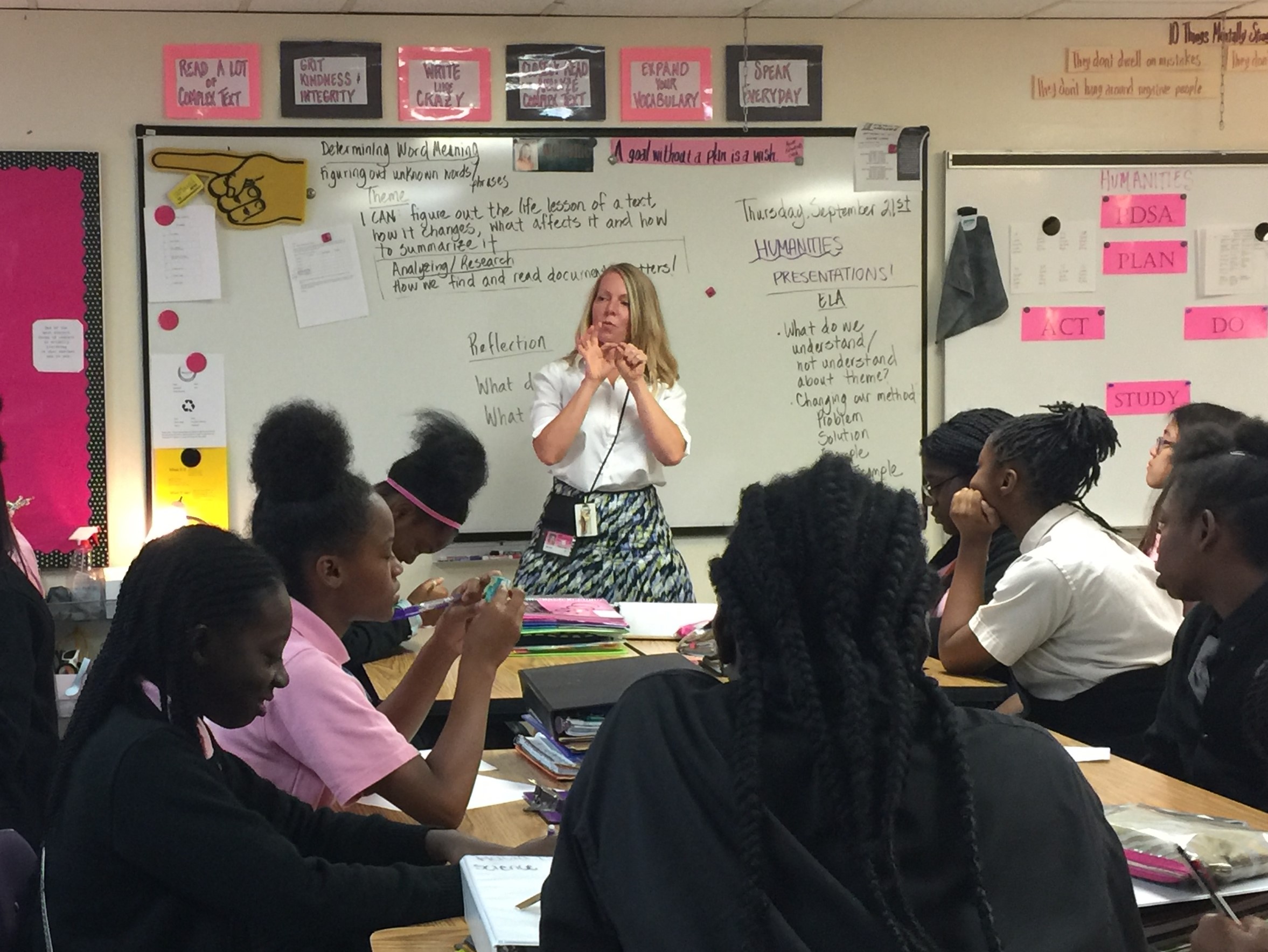

Principal Stephanie Patton of the Columbus Preparatory School for Girls is relentless in her mission to give her middle schoolers the same opportunities in their urban public school as students receive in the most privileged private schools. She decided to send CPSG teacher Pam Reed to my workshop to develop a pilot using the Korda Method in her 8th grade humanities class. Pam is no stranger to working with disadvantaged pupils. In her two decades of teaching she’s worked primarily with rural and inner city students. Teaching them history turned out to be an uphill battle and she struggled with how to get her class engaged with the material while simultaneously accomplishing the learning objectives set out by her curriculum. After implementing two pilot projects in her fall humanities class, Pam sat down with me to discuss the pilot program she’d just wrapped up and how it’s changed her idea of her role in the classroom.

Doris: Can you please start by telling folks about yourself and then what brought you to the workshop?

[1:02]Pam: Yes. So my name is Pam Reed. And I’ve been teaching in Columbus City Schools for 20 years. I love everything about urban education. I came here to Columbus City Preparatory School for Girls.Our school started in 2010. We’re one of the few urban middle schools for girls in the country. We basically take girls as a lottery system from all over the city.I teach 8th grade English. This year we are starting an 8th-grade humanities class, which I got to write and teach.

Doris: So you came to the workshop. Talk about what that did for you and what you came out of it deciding to do.

[3:19] Pam: Well, as a teacher, I’ve always been a risk-taker. So if there was something that was new or innovative I was always willing to try it. And coming to the workshop, I had no idea to be honest with you what to expect. I thought it would be a sort of pre-packaged, “here’s what you do” deal. When we did the business model I could see that becoming a problem-solving framework for how my students could look at situations in history or current events.

Doris: Can you describe your class a little and how you set up your pilot?

[5:20] Pam: I have 31 girls. So I dissected all of my curriculum. And I still couldn’t wrap my head around, “how do I get them to care about history”? I want them to make connections between what’s happened in the past and what’s happening today. So my student-teacher and I, we found 40 of what we thought were the most important events of the 21st century. Everything from the minimum wage gap to the Pulse Nightclub shooting to the transgender military ban. And we found pictures. We just started out with pictures.We set up the library with the pictures all around the room and a placard that described what the event was. Just, “Pulse Nightclub shooting,” and that was it. The girls would go around and they examined everything. They took notes on what they saw. They used their phones to do research. Then they had to pick one event. The next day we did a problem pitch. I was so not sure how this would work.

Students voted for the problems they cared most about and formed teams to solve them. They had three weeks to prepare their solutions to present to a panel that would include a professor from Ohio State University with subject matter expertise. In preparation, they had to race to develop their solutions, which had to be evidence-based, including an exploration of the historical context resulting in the contemporary problem.

I mean, the clash at Charlottesville was one. They did a ton of research. It was the research that impressed me the most because I gave them no direction. So what they came in with were stories of people who were involved in Charlottesville or how the minimum wage actually affects a single mother or things that I just didn’t think about. And man, they were a very diverse group of topics.So after they refined the problem, they started coming up with a viable solution. Part of that was looking at the past of the problem. So they had to take the problem they came up with- the wage gap for example – and they had to trace it back to its roots. And that seems like a simple thing but to look at the timeline of an actual historical event or an idea or an issue in this country is a pretty big order.

MY GIRLS WHO LOOKED AT BLACK LIVES MATTER, THEY TOOK IT BACK TO SLAVERY AND THEN THEY LOOKED AT HOW WE’VE HANDLED ISSUES WITH RACIAL INEQUALITY IN THIS COUNTRY SINCE THEN. IT WAS MORE REFINED THAN JUST THE TIMELINE. THEY ACTUALLY LOOKED AT THE NUANCES THAT HAPPENED AT EACH STEP AND HOW EACH STEP BUILT ON THE PREVIOUS ONES SO WE GOT TO THE PLACE WHERE WE ARE NOW.

Doris: Which is so interesting. So most of the students are African-American themselves? Yes. And as somebody who’s trying to teach history in these four weeks you didn’t get to decide what parts of history they were going to cover, did you?

[14:55] Pam: Nope. It’s far more meaningful and impactful than anything I could have taught them, far more. And if they could make connections to the news they would come in and say, “I saw this thing on the news.” They’re still building forward the idea they originally had. None of them went in the direction they thought they were going to initially. It’s different for me in every way possible. I’ve never been a by-the-book teacher. I’ve always created everything that I was doing and I’ve never used a textbook. I’ve never been a teacher like that. But it’s Deschooling me after 20 years of teaching.

THIS BREAKS ALL THE RULES OF TRADITIONAL EDUCATION AND IT FEELS FREEING. IT FEELS LIKE I HAVE PERMISSION NOW TO TEACH THE WAY I’VE ALWAYS WANTED TO TEACH.

Pam: I can hit all my objectives. And it’s completely rigorous. The challenge is absolutely there in my class. I can think of one group in particular when I would just walk over to do check-ins with them. They were so intent on where they were going. I’m not going to say I was inconsequential, but they don’t need the structure. They made their own structure. It was very eye-opening to me. I had some girls who still craved asking the questions and wanting a little guidance. But most of the girls they just want the space. Yeah, it’s funny. For years I’ve talked to my student-teachers about teaching being smoke and mirrors, where you have to manipulate things behind the scenes. But this has shown me – and it should show every educator.

WHENEVER WE THINK ABOUT THIS GENERATION, WE THINK THAT THEY DON’T CARE, THEY’RE TUNED OUT, THERE’S NOTHING THAT MATTERS TO THEM. BUT THEY DO! THEY CARE SO PASSIONATELY. THEY’RE JUST LOOKING FOR A WAY TO SHOW THAT THEY CARE.

Doris: So in two weeks these 14-year-olds are coming out of it with that nuanced understanding. And how great is that?

[32:33] Pam: Well, if I were an employer in the future or a college doing admissions and I had kids who could critically think, who can analyze things, who can work in teams, these are so much better than regurgitating some historical facts or regurgitating the fact that, you know, this happened on this date and this… There’s way more critical thinking. I can say that for sure compared to what I’ve done in the past. I love being a writing teacher. And so that part will never go away but I can get them to write so much deeper and they actually care about what they’re writing about, versus it’s just an assignment. I’m hitting all the content in the curriculum I need to hit.

THERE’S NO PART OF WHAT I’M DOING THAT’S LEAVING ANYTHING BEHIND. THERE’S NO PART OF WHAT I’M DOING RIGHT NOW WHERE I GO HOME AT THE END OF THE DAY AND QUESTION AND SAY “I REALLY WISH I WOULD HAVE DONE THAT BETTER”.

Pam: I’m learning to let go of perfectionism with education in that class because it’s free-flowing. It’s a fluid class. And it’s not about me.